Steps for successful interdisciplinary research on extremism or disinformation

The need for successful collaboration in this space is critical, so here’s how to make it happen.

Between 50% and 75% of all inter-organizational collaborations fail. That failure rate does not specifically consider partnerships that require people to look at deeply disturbing content. It’s fair to guess that this added stressor wouldn’t improve a project's success rate.

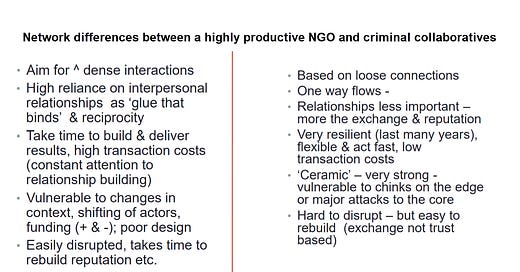

Collaboration brings together disparate and often previously competing groups together to achieve what can’t be delivered by working alone.

Still, the need for successful collaboration is great, and success will be needed to address the converging crises in society today, so here’s how to make it happen.1

Setting up

1. Make sure you actually need to collaborate and that cooperation and coordination won’t suffice.

2. Understand that collaboration is risky.

3. Find the right partners.

4. Leverage relationships.

5. Find common ground with the other parties.

Making it work

6. Invest in relationships.

7. Identify and support champions and sponsors.

8. Close down the ineffectual or toxic — and have each others’ backs.

9. Protect the fortress.

10. Measure, monitor, and communicate success.

Setting up

Make sure you actually need to collaborate and that cooperation and coordination won’t suffice.

Don’t be lured into collaboration because everyone else is doing it. More names won’t make your work better — collaboration might. Collaboration is only worth the hassle if you need it, especially if it’s interdisciplinary research.

Disciplinary research requires less trust and can tolerate less communication and more strain. This likely relates to parties having similar education and experiences related to the research topic. Often researchers within a subject matter share a culture, complete with jargon, assumptions, and expectations for one another. Most importantly, researchers with expertise in the same subject are qualified to truly check each other’s work.

Interdisciplinary work requires intentional effort, thick communication, understanding of how parties’ objectives differ, and a high degree of trust.2 Here, one usually cannot vet other researchers’ work to the same degree, and people’s education and related experiences likely differ. You must trust others’ judgments in a way you do not need to with disciplinary research.

Collaboration is risky.

Collaboration is not business as usual. By definition, it is risky and represents a different way of working. Relationship development is typically not well-supported or prepared for, so don’t expect someone else to explain or address this with your interdisciplinary team.

Ideal collaboration relationships take three years to establish but don’t panic if you don’t have years behind you.

History isn’t always possible, and projects can succeed without it, with special attention to other aspects listed.

Prioritize relationship-building and be aware of the weaknesses that this unfamiliarity brings to a project.

Take time to review the proposed collaboration and determine the costs/benefits:

What might you lose, and is that acceptable to you?

What is unacceptable?

Is the effort likely to produce a dividend of sorts?

Find the right partner(s).

This might seem like a no-brainer but choose poorly, and your collaboration may be doomed from the start. Mismatched expectations and goals or working with parties that don’t have the right skills and resources could be a recipe for failure. The right partners don’t necessarily have to be like you, but you must be sure that the other parties respect your way of thinking. There must be a willingness to discuss and resolve those differences.

There’s no point in collaborating with interdisciplinary partners who don’t bring additional expertise and resources to the table.

While you absolutely should cultivate a relationship with partner researchers, if the primary payoff you see is getting to work with friends, this is not a collaboration and may be unwise.

Collaborate for the right reasons.

A project might require new ways of thinking, different skill sets, and different resources.

Will your new partner(s) have to teach you or you them?

Will past methods work here, and if not, are you developing them?

Where are resources coming from, and who is funding that?

Leverage relationships.

Collaborations (specifically interdisciplinary) work best when you work with people you know and trust and where time has been invested in building relational capital.

For example, it is not uncommon for potential collaborators in the fields of law or medicine to spend significant time considering different people or organizations for partnerships. There’s a reason. These fields require real trust, but so do a lot of others that we ignore at our own expense. Take it seriously.

If you need to hide something serious related to the research from your collaborators:

That may be unethical, especially if it could negatively affect them

The requisite trust does not exist and will either need to be cultivated or the project canceled

Find common ground with the other parties.

When you’ve got a fair idea of your ideal collaborators (or at least narrowed it down to a handful), negotiate the terms of the agreement upfront. Terms should include: How, on what, and for how long you intend to work together. Will your research partner pick up the phone in 5 to 10 years because you have a question about your work together?

Collaborations take time to establish, so ensure all parties invest in the same goal.

This doesn’t have to be etched in stone -- simply communicating that there is uncertainty works too.

Discuss how conflict will be handled — yes, you will have conflict, and if you can’t talk about it now, stop your project while you’re ahead.

You don’t need a manual or lengthy treatise, but it is important for parties to fully understand everyone’s interests and responsibilities.

Spend time establishing the ground rules — that’s your foundation.

Do not assume your collaborators have the same thresholds for stress, communication, the strength of evidence, patience, time, cost, or anything else.

Do not assume complex values such as ethics are the same. Discuss them.

Making it work

Invest in relationships

Has this begun to sound repetitive? Good, then you’re getting the message. Interdisciplinary collaboration is based on relationships, not programs or organizations.

It’s not simply a transactional arrangement.

If you want a transaction, hire a consultant — seriously, just pay someone.

“For collaborations to work, you need to establish face-to-face relationships initially to build relational strength. Face-to-face meetings every so often between collaboration partners also help to ensure that things run smoothly. Simply put, time is a big part of the investment.”

— Keast

Identify and support champions and sponsors.

Collaborative projects work best when there is a champion3 (usually from industry) who knows exactly how the research will benefit his/her organization, industry, or sector.

Your champion might be a shared employer, mentor, or something else entirely.

Figuring out who your champion is can be as simple as asking who is funding your project, but it’s critical that this occurs in an ethical framework.

Shut down the ineffectual or toxic — and have each others’ backs

One of the better ways to illustrate what a successful collaboration needs is to show what it is not.

Some collaborative projects end up weighing on key project partners. That strain affects everyone else and can affect relationships that would otherwise be productive. If you’re slacking, you’ll eventually pay through either a failed partnership or a poorer overall outcome.

Call out toxic behaviors and be willing to be called out

If that doesn’t work, revisit previous agreements outlined at the beginning of the partnership.

This doesn’t mean you end the project because someone had a bad week or forgot a meeting.

Consider asking how you can help someone before accusing them of a shortcoming.

Examples of toxic professional behavior include:

Narcissism: “Nobody can do what I do”

If you could do this project without collaboration, you probably would. Don’t forget that.

Workaholics: “I don’t leave the office before 9 pm”

Not only are they prone to burnout, but they make fatigue-related mistakes and may generate resentment in a team by exerting disproportionate influence over a project.

Be culturally sensitive here because different cultures place professional work at various levels of importance.

Know-it-alls: Those who have an answer for everything and refuse to accept or even listen to a different point of view.

These are particularly damaging in collaborations.

There wouldn’t be a collaboration if one group member had all the necessary skills, resources, funding, and bandwidth to manage it, so in the act of forming a group, you’re acknowledging a need for one another.

Protect your foundation.

Understand your partners’ work, strengths, and weaknesses. Use these elements to find ways to encourage and support each other. Weaponizing a collaborator’s weaknesses is toxic behavior, and the tolerance for it should be zero.

To keep a collaboration successful, you must be intentional about your approach, and that means not taking inevitable frustration out on your partners.

Example: distractability

Collaborative - asking if you can plan a time of day that is easier to focus on, trying different meeting formats, considering whether distractability has to do with outside circumstances that require compassion.

Toxic - exploiting that weakness to your personal career advantage or using knowledge of personal weakness to insult or lash out at one another; complaining about a shortcoming of one partner to others.

Specifically, in areas of extremism and disinformation research, manipulation and targeting are real operational security concerns.

Share concerns with your team.

Understand methods that could be used to thwart your research, like driving a wedge in the project or mischaracterizing your work.

Measure, monitor, and communicate success.

You need to establish a clear way to measure your tracking against previously agreed objectives. Ask, “How will we know if this is a success? What measurable benchmarks could we set?”

How will you demonstrate clearly and unambiguously whether the project (or a step in the project) was a success or whether it fell short in some areas?

Measuring and communicating what success looks like is essential to keeping a collaboration going and – more importantly – working out whether it’s on the right path or needs work.

The need for course correction should not be seen as a failure but rather successful monitoring and problem-solving.

Researching extremism or disinformation

Especially when working with violent extremism, the number of people who can understand the content you see regularly may be limited to those on your team. Looking at content created by neo-Nazis or ISIS is not normal, and it will affect you. Acknowledge this from the beginning.

Make time to listen to and take the time to check on one another.

Discuss changes you are seeing in one another if that is happening.

Know what it looks like when people on your team are stressed, and understand that researchers can develop PTSD.

"There's no actual training for what might happen to you. What you might go through by constantly being exposed to this kind of content over a long period of time."

— NPR

While professionalism is sometimes defined by formality, that isn’t what it means: “the competence or skill expected of a professional.” Having that skill does not lead us to cease being a person.

A job that requires people to face content that may be deeply personal and disturbing requires a different approach. You must support one another.

People will be comfortable with sharing varying degrees of their lives with one another and context is important.

No one should ever feel obligated to share personal information or details.

No one was made to endure this and, least of all, alone.

An article by Dr. Charles, M., & Keast, R. (2016), formed the basis for this outline.

MacLeod, M. What makes interdisciplinarity difficult? Some consequences of domain specificity in interdisciplinary practice. Synthese 195, 697–720 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-016-1236-4

Champion, sponsor, employer, patron -- any of these terms could describe this role. Figuring out who this party is can be as simple as asking who is bank-rolling you and why (ensure there are no strings and that if there are, everyone understands and that expectations are not ethical or legal violations).