Anti-abortion groups decried the repeal of a rule that increased abortions by 40%

The policy increased abortion rates by 40% in countries most affected by defunding following implementation of the Mexico City Policy.

How the Policy Affected Rates of Abortion

While anti-abortion groups favor the Mexico City Policy, comprehensive analyses using long-term data from many affected countries show the policy—intentionally or not—increased abortion rates.

When comparing countries most affected by defunding to those that were least affected, like those that receive from other sources, we saw the abortion rate increase by at least 40% — as a conservative estimate.

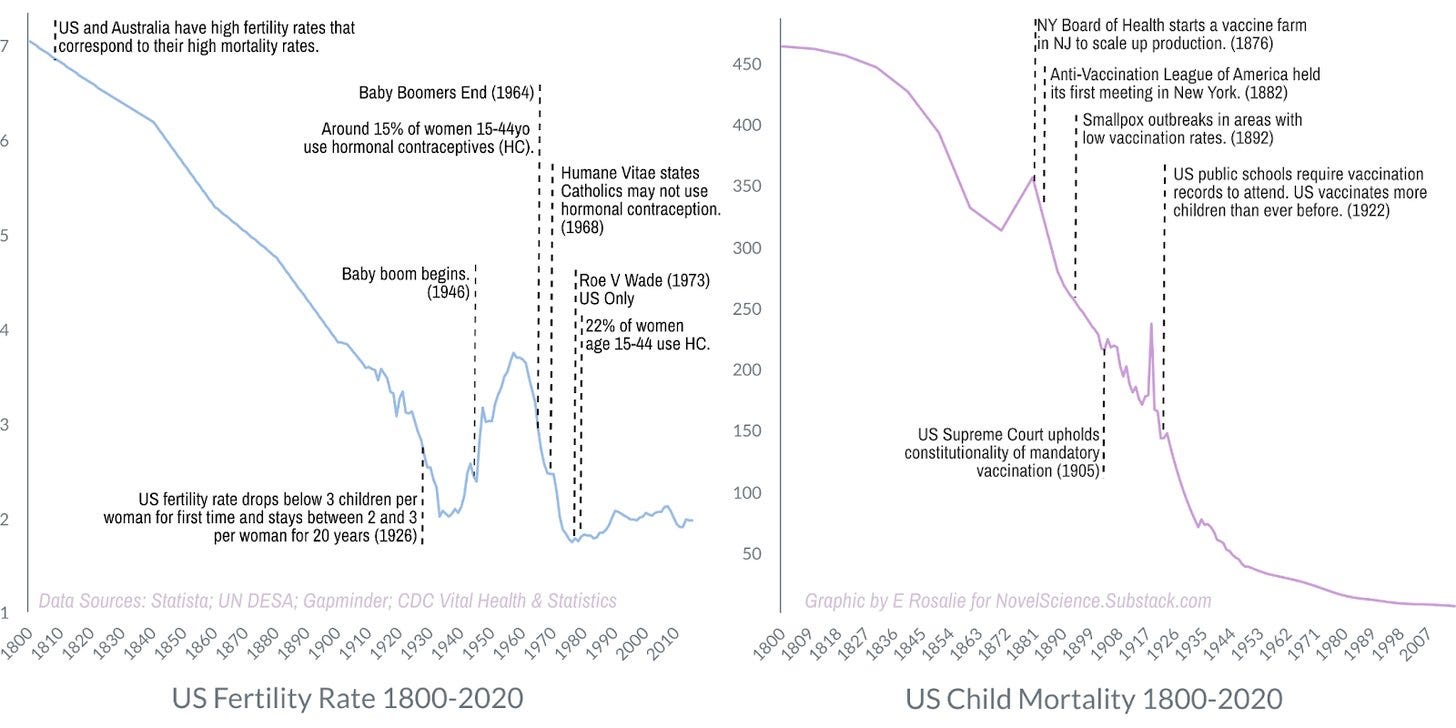

Put another way, in the countries that relied the most on US funding for global health initiatives, the Mexico City policy made abortion rates soar. Areas without funds to provide family planning services like contraception or education about fertility meant no access to contraception. That meant more pregnancies in locations where childbirth poses a significant threat to life.

Origins of the Mexico City policy

Under President Ronald Reagan, the US added the Mexico City policy, a requirement that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) could not “perform or actively promote abortion as a method of family planning” using funds, regardless of the source, as a condition of receiving funding from the US government.

If an NGO could not or would not agree, that meant possibly losing funding for all of the NGO’s efforts. The US funds global health NGOs— for both altruistic and selfish reasons — that provide aid globally. Requirements for funding recipients related to abortion have changed back and forth since the Reagan era.

While the harm it has done is far from desirable, this on-and-off style policy means we can exclude other explanations more easily, and the evidence showing the rise in abortion rates holds more weight.

President Clinton repealed the policy; Bush reinstated it. Obama repealed it. Trump reinstated the policy and significantly expanded the definition to encompass the vast majority of US global health assistance. The change included programs like PEPFAR, maternal and child health, malaria, nutrition, and others. Biden removed the restriction.

What Research Shows About the Mexico City Policy

Again, this policy was shown to dramatically increase the rate of abortions in the most affected countries, and the consequences of that go beyond the abortion issue itself.

For women who already had several children in regions where food and opportunities were already scarce, for example, the choice may have been between potentially dying in labor, dying while attempting to terminate the pregnancy, or surviving with another child that they were unable to feed.

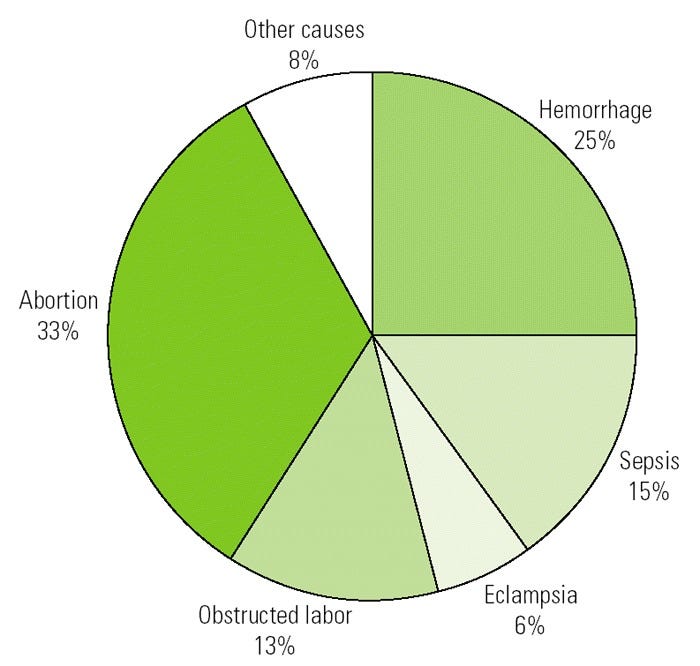

The main direct causes of maternal deaths, accounting for up to 80 percent of cases in Africa, are obstetric hemorrhage, puerperal sepsis, pregnancy-induced hypertension (including eclampsia), obstructed labor and ruptured uterus, and complications of unsafe abortion (see graph). Three causes—hemorrhage, sepsis, and eclampsia—account for a vast majority of deaths, considering that even some cases of abortion or obstructed labor eventually succumb to either bleeding or sepsis.— Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa1

Further rejection of the evidence raises questions about whether there is an alternate motivation or a lack of concern with whether the measures promoted have the intended effect. It’s difficult to understand.

No one wants to see abortions increase. When we look at the countries with the lowest rates of abortion, there is a commonality. They have unrestricted access. It’s a counterintuitive result, but that does not mean it’s incorrect.

Checking your work

A way to check if the relationship is as it appears would be to look at it in reverse. Indeed, the trend operates in the inverse. Countries with the most extreme restrictions do not have lower abortion rates. Instead, they simply have higher rates of unintended pregnancies and worse outcomes for mothers — more deaths or permanent harm.

Unintended pregnancy rates are highest in countries that restrict abortion access and lowest in countries where abortion is broadly legal.

Perhaps the results are unexpected—certainly, one could have seen them going the other direction—but this is why science has such value.

Checking results allows us to do better; the anti-abortion movement can do better if it wants. The question becomes then, does it wish to see fewer abortions, or does it wish to refuse to be wrong.

The intent of the law may have little to no effect on the consequences. Policy is complicated, and whether a specific approach brings about the desired results is far from certain–this is the problem of policy-writing and why expertise in policy and not ideological motivation ought to be our guiding principle.

“Restrictive abortion laws are not associated with lower abortion rates” (Faúndes and Shah 2015).

Data, across time, geography, organization, income, access, and more, tell us the same thing: The overturn of Roe v. Wade isn’t just unlikely to reduce the number of abortions and increase the number of far-more-dangerous late-term abortions by as much as 500%, as it has in Poland (Bennhold and Pronczuk 2022; Sedgh et al. 2012).

“Homicide is a leading cause of death during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the United States. Pregnancy and the postpartum period are times of elevated risk for homicide among all females of reproductive age” (Wallace et al., 2021). Still, we recently saw resistance to renewing protection for the precise demographic that faces this risk

Responses to repealing the global gag rule

Biden repealed the restriction in January 2021. He has come under harsh criticism from anti-abortion groups that have published headlines like:

Biden’s first weeks in office have been a gift to Big Abortion

Abortion activists make dubious claims to promote funding abortion overseas

Abortion supporters in Congress want to force American taxpayers to fund abortion overseas

The articles contain misleading claims and, in some cases, disinformation. “Big Abortion,” like “Big Pharma,” can be a rhetorical device to cast doubt without providing actual evidence. The use of the word “gift” is vague, so without further information, one couldn’t know what Biden gave anyone. It suggests a relationship, since we give presents to people we like, generally.

Rather than inform—a possible title might read “Biden Repeals Mexico City Policy”—this shapes the viewer’s perception. It doesn’t tell a reader what happened; it tells them how to feel about it. Then, it tells the reader only the part of the story that will lead them to feel as the headline indicates they should.

The poor reporting in the article seems unlikely to be aimed at informing the reader. That leaves the intention to influence or a strong, unconscious bias that should have been corrected by an editor.

In 2019, when research showed the unintended, extreme increase in abortions in countries affected by the policy, anti-abortion activists rejected the study quality stating it was methodologically weak. It’s possible, but they fail to clarify how and what effect that might have on the results.

The website closed by offering a suggestion to improve the study quality.

“A stronger study would also consider data after 2008 to see if overseas abortion rates fell after the Obama administration rescinded the Mexico City policy.”

The suggestion about improving study quality is good, and I’ll address that in the next section. However, claiming the stark difference between the policies on and off periods is proof that the study can’t be correct is illogical.

Discounting numbers that feel unbelievable will vary by the person looking at the data. This method of assessment is, by definition, unreliable.

This is an unacceptable justification, as it does not show the results are unreliable.

More importantly, the author appears to dismiss clear evidence of harm, something an ethical scientist cannot do. This is a bias known as cherry-picking, where we select evidence that supports our claim.

As for the earlier critique, which was valid, the researchers published a study that did precisely what the anti-abortion website had recommended. The results were similar and included data from Clinton, Bush, and Obama. The authors took great care to include only what could be shown concretely, and as a consequence, these estimates are almost certainly lower than the true numbers.

To date, no one has been able to explain why the study isn’t valid or raise a concern that casts doubt on the findings.

Rogo KO, Oucho J, Mwalali P. Maternal Mortality. In: Jamison DT, Feachem RG, Makgoba MW, et al., editors. Disease and Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2nd edition. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development | The World Bank; 2006. Chapter 16. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2288/