New Study Says Insensitivity to Evidence Rather Than Inflated Confidence Explains Dunning Kruger Phenomenon

Researchers tackled criticisms and concerns from past studies.

New light on the Dunning-Kruger effect1 (DKE) came on Feb 25, 2021, when researchers tackled criticisms and concerns from past studies. In the landmark paper Unskilled and Unaware of It (1999), Dunning and Kruger wrote about a phenomenon where people who knew the least were among the most confident and stayed confident because they did not understand how little they knew.

It’s the adage “You don’t know what you don’t know.” Critics have asserted that the idea is elitist or that study design is responsible for study results rather than DKE, but this latest study supports the idea that DKE exists.

“Not only do these people reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the metacognitive ability to realize it.”2

What caused DKE wasn’t clear but the original paper scored people on their abilities and intuition in humor, grammar, and logic. People who landed in the lowest 25% of scores overestimated their abilities to an extreme degree. Though they ranked in the 12th percentile of scores, they estimated their abilities at around the 60th to 65th percentile.3

The New Study

Insensitive to Evidence

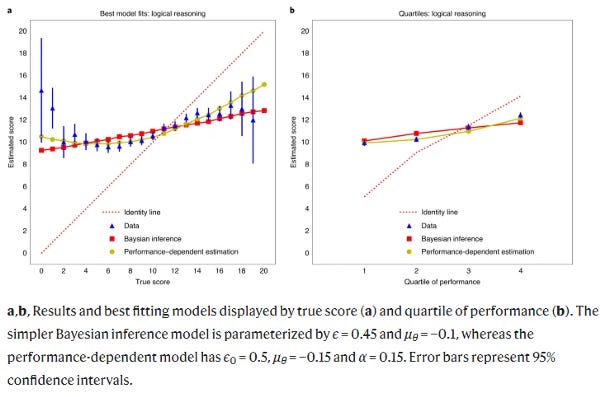

The blue line shows how a person performed and the red line shows how they assessed their own abilities.4 One could argue the results are because of the study design and not a real phenomenon, but that doesn’t appear to be the case looking at the evidence from Jansen et al. (2021).

People with lower scores overestimating their abilities could be explained in two ways:

Existing beliefs about their abilities informed how they self-assessed rather than how they performed on the task.5

When a person’s ability to determine whether they answered correctly is limited, they might overestimate their skill because they know too little to understand how poorly they performed.6

Another way to say this would be that insensitivity to evidence led people to overestimate their abilities. Jansen et al. “provides support for low performers being less able to estimate whether they are correct in the domains of grammar and logical reasoning” (2021). An alternate explanation that doesn’t include an inflated ego:

Most people judge themselves as better than average. In the absence of evidence that has meaning to the person, perhaps that default remains. 7

Results Versus How People Judged Their Performance

Jansen et al. propose that people with low scores may misjudge their abilities for the same reason their performance was poor, insensitivity to evidence. They’re insensitive to their poor performance because they knew too little. The evidence has no meaning and so it doesn’t factor into their self-assessment.

Pop-culture writing on DKE often has a condescending and inflammatory quality, insinuating that the phenomenon flows from hubris. Indeed, when a leader exemplifies DKE the results can be catastrophic, but we should avoid injecting how we feel about the impact of DKE on society into research and conclusions drawn.

If poor performers over-estimate their scores as slightly better than average, something people commonly assume about themselves, it could at least partially explain the phenomenon.8 This “default” view of a better-than-average self might stay in place because the evidence—that they were doing poorly on the test—was something they could not see.

Dunning, D., Heath, C., & Suls, J. M. (2004). Flawed self-assessment: Implications for health, education, and the workplace. Psychological science in the public interest, 5(3), 69–106.

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Ibid.

Jansen, R.A., Rafferty, A.N. & Griffiths, T.L. A rational model of the Dunning–Kruger effect supports insensitivity to evidence in low performers. Nat Hum Behav (2021).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Zell, E., Strickhouser, J. E., Sedikides, C., & Alicke, M. D. (2020). The better-than-average effect in comparative self-evaluation: A comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(2), 118.

Ibid.