Are We Looking At Vaccine Hesitancy the Wrong Way?

Different variables affect vaccine hesitancy similarly. This may suggest it's less about the specific variables and more about the stress they generate, which influences our thinking.

The Many Drivers of Vaccine Hesitancy

Vaccine hesitancy varies widely depending on income, education, political party, religion, and more.1 This makes it hard to make generalizations, and different variables are capable of causing the same hesitancy.

This may suggest that a stressor's effect on decision-making affects people in these groups rather than the variable causing the stress as being uniquely able to cause vaccine hesitancy.

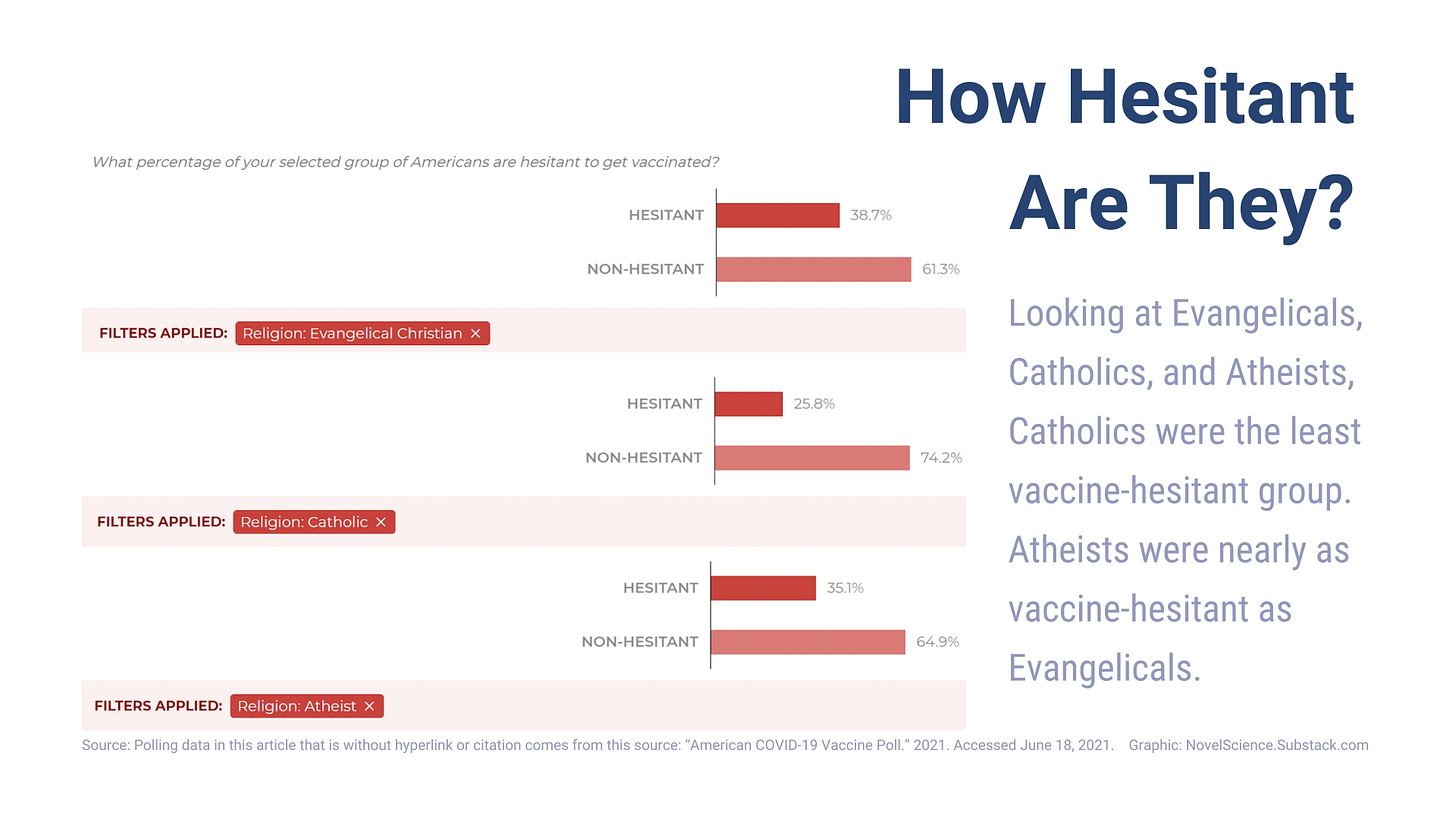

Evangelical Christians have been a consistently vaccine-hesitant group.

Religion itself does not appear to explain the hesitation: Catholics have a far lower vaccine hesitancy than Evangelicals.

Evangelicals differ from other Judeo-Christian religions in their tendency to wrap science in with religion and politics far more than Catholics, Jewish, or Protestant groups. Protestants were less hesitant than Evangelicals but more so than Catholics.

Data on Hindu, Muslim, and Jewish people were too few to examine these groups.

For atheists, the data show a lower vaccine hesitancy than Evangelicals, but not as low as the hesitancy among Catholics.

Looking at Evangelical Christians who identify as Democrats, who would thus be unlikely to support Trump, one can see a staggering difference in vaccine hesitancy from Evangelical Republicans.

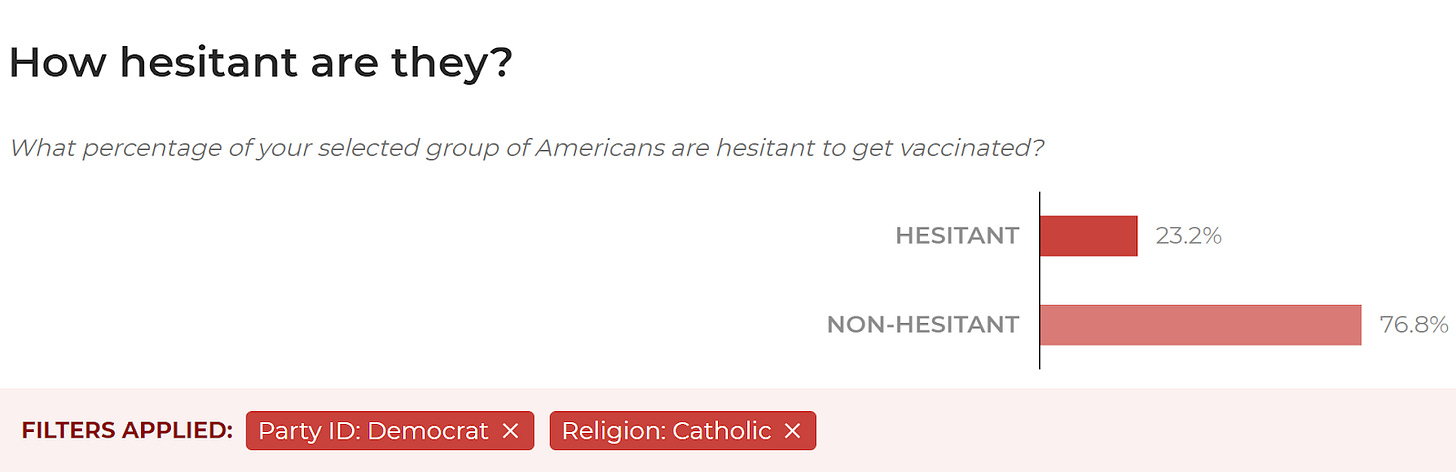

Interestingly, the difference between Catholic Republicans and Catholic Democrats was only about 5 points between parties.

Evangelical Christians differ by 20 points between parties.

Something happens at the intersection of Evangelicalism and the Republican party.

Catholics had some of the lowest vaccine hesitancy with 23% for Democrats and 28% for Republicans.

Religion is not the determining factor, but perhaps neither is Republicanism.

Republican Catholics have a greater likelihood of vaccine hesitancy, but it is nothing like the difference between Evangelical Democrats and Republicans.

This quashes the notion that religion or Republicanism can fully explain vaccine hesitancy. That still leaves what is driving it unanswered.

Nonpartisan Modern Medical Miracle Goes Partisan

Previously, vaccines were not particularly partisan. Answering how and why vaccine attitudes rapidly shifted may hold answers to our vaccine disinformation crisis.

Counties that voted for Trump in the 2020 election are some of the most vaccine-hesitant, but states that went to Romney in 2012 had some of the lowest vaccine exemption rates.

This is not a precise comparison, but it does suggest that attitudes have and are changing quickly.

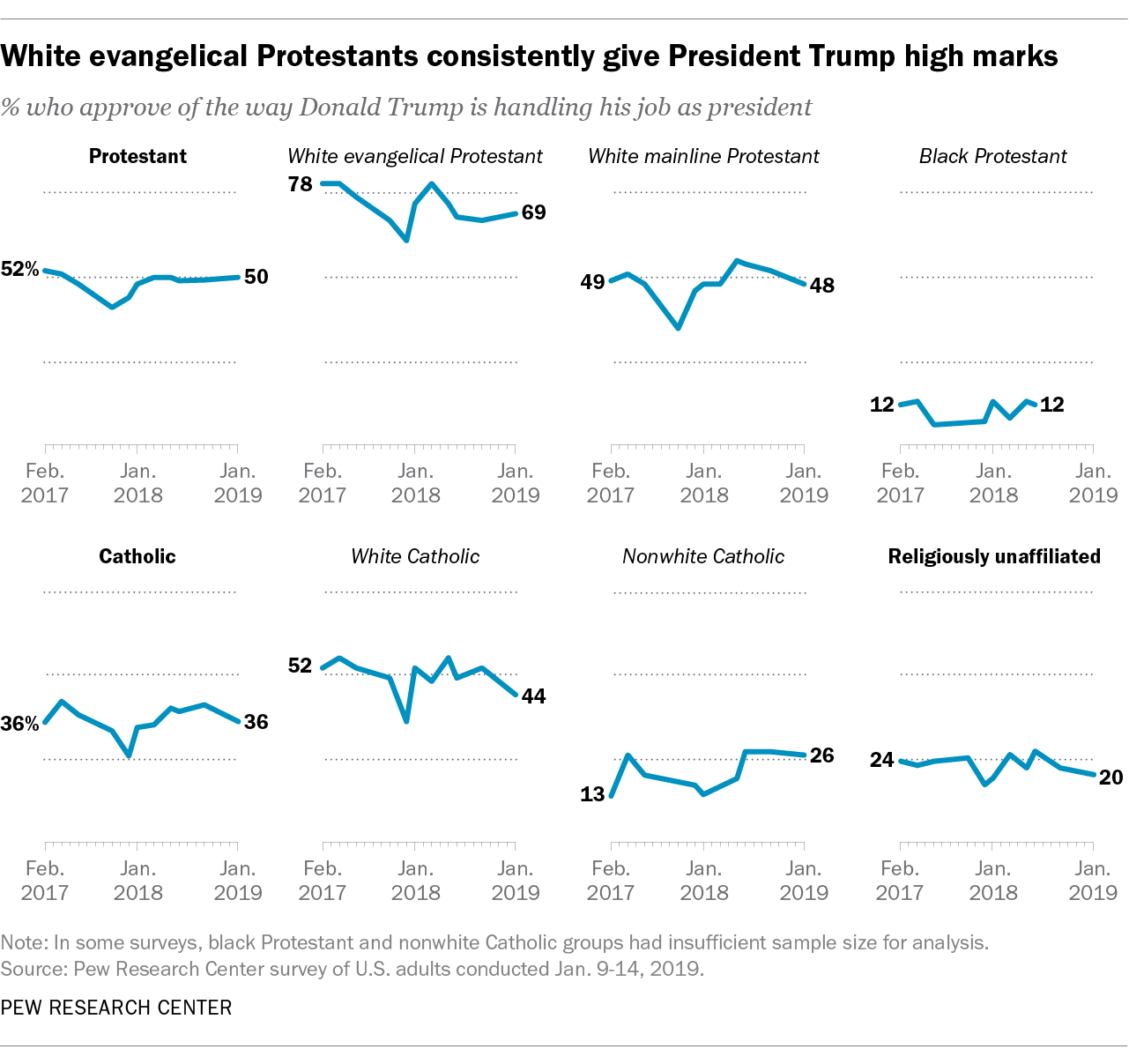

Given that Evangelical support for Trump was extremely high in comparison to other religions, it would seem logical to explore whether Trump himself has the greatest impact on whether or not someone is vaccine-hesitant.

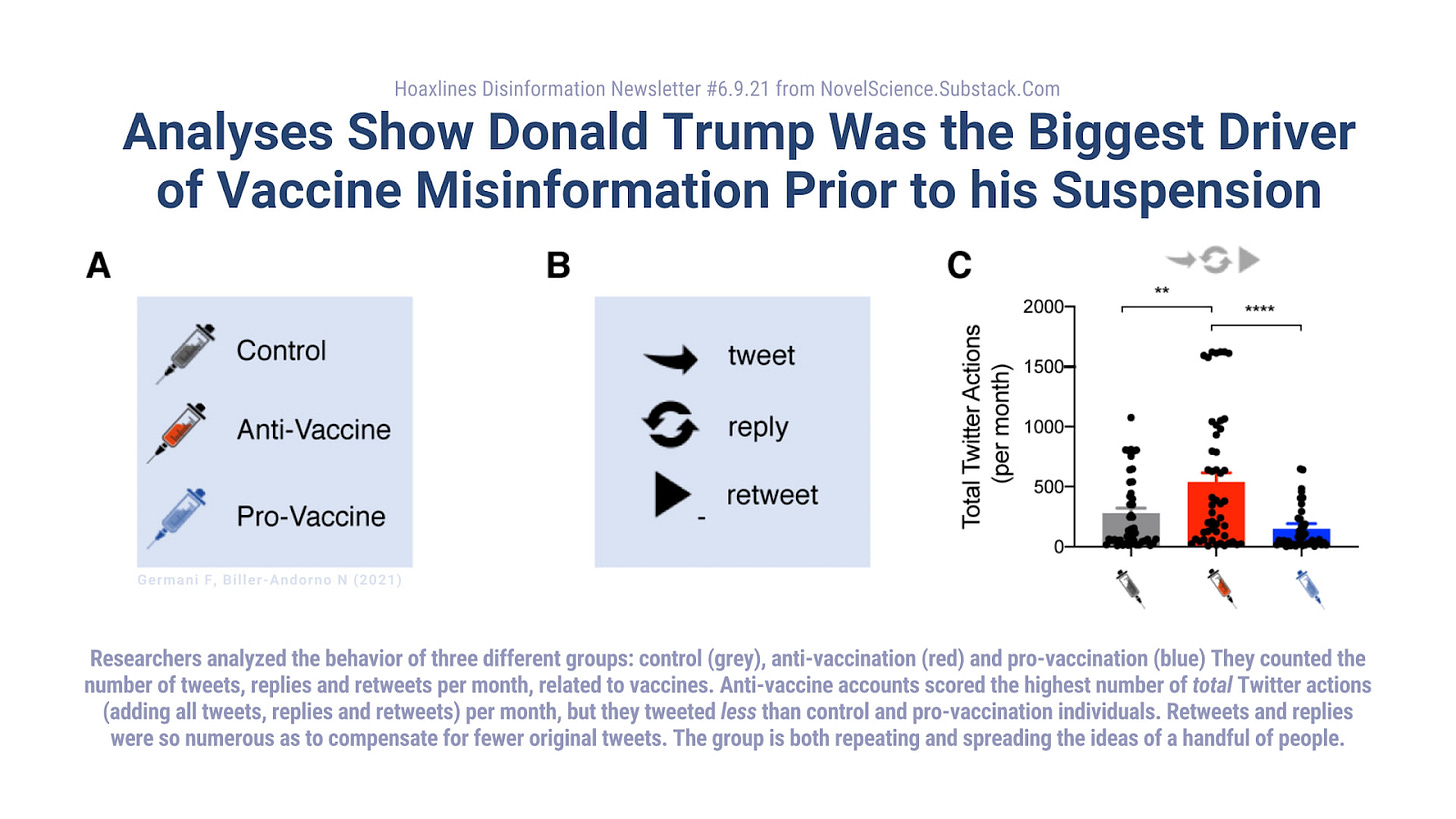

Studies have shown that before social media gave him the boot, Trump was the largest source of vaccine misinformation.

He was also the largest source of misinformation more generally.

The data show that Trump-voting counties are most closely associated with vaccine hesitancy.

Researchers examined what affects how susceptible we are to disinformation and found that the “uneducated Trump voter” trope is not evidence-based, nor is the assumption they are financially disadvantaged.

We know that intellect and education are two variables affecting whether someone believes misinformation. Educated, intelligent people fall for it. A big factor in whether we believe mis- and disinformation is whether we want the story to be true.

Pew Research polling finds that Democrats and Republicans have similar levels of scientific understanding. Still, Republicanism was a strong predictor of vaccine hesitancy, but dividing groups by income, education, and religion increased or decreased how reluctant people were to vaccinate.

Having similar levels of scientific literacy, however, does not mean that everyone holds evidence-based views.

Trump Seems to Mediate Vulnerability to Misinformation

People who like Trump are at an increased risk of believing false claims because of Trump himself. Before Trump mediates that increased vulnerability, other traits, like how we gather information, come into play.

Republicans who do not approve of Trump differ significantly from those that do. In fact, a longtime Republican pollster identifies five types of Republicans.

The Infowar GOP (Ron Johnson, Matt Gaetz, Marjorie Taylor Greene), the Never-Trump (Mitt Romney, also known as RINOs), the Post-Trump GOP (Kinzinger, Cheney), Trump Boosters (Lindsey Graham, Mitch McConnell), and Diehard Trumpers (Mike Pence). Intuition-based thinking makes people more likely to be Republican, which makes them more likely to approve of Trump, who then increases their risk of believing misinformation because they trust him.2

In the past, one could find both types of information gatherers in both major parties. Today, the ideologies of the parties differ starkly, but so too does the way they gather information, which only magnifies the differences.

Embracing Trump specifically requires embracing purely intuition-driven thinking and a rejection of evidence-based information gathering. Highly complicated, population-level effects like what a policy will do downstream, are not ideas that lend themselves to intuition-based thinking. The consequence of this can be seen in popular support for actions that are largely symbolic.

People who support these symbolic measures may assume they are effective because it’s “common sense,” as with the border wall—a solution that is so universally accepted as unlikely to affect the situation that most conservative think tanks had a negative view of it.

This does not mean it does not have political capital. It can be a unifying rallying cry.

Education greatly impacted hesitancy among those earning under $50,000/yr, but even without an education, people earning $80,000+/yr are more accepting of vaccines. Income (scarcity and stress) affects our ability to think and our executive function.

Executive function—essentially self-regulation—is how we go from knowing what we should do and doing it.

Financial strain negatively affects decision-making. This makes cycles of poverty harder to break, and it may make people more vulnerable to misinformation and schemes intended to exploit them, like predatory lending.

Our information gathering, assessment, and quality of our decisions are not static. They can change over time.

Perhaps income decreases hesitancy because it reduces the financial strain that negatively affects decision-making. This explanation makes more sense than saying it’s education because the difference between these groups isn’t higher education. It’s income.

Related read: Poverty can sap people's ability to think clearly

Related read: Poverty's Impact on Children's Executive Functions

Education has a major effect on vaccine hesitancy, and that may suggest there is more than one way to combat vaccine hesitancy:

Address the mental strain that leads to poorer quality decisions

Education, which makes people aware of the limits of intuition-based thinking and improves critical thinking.

College-educated people with lower incomes do still arrive at vaccine acceptance. Studies show critical thinking improves during the normal college experience. Does this mean that education can help people overcome the mental obstacles thrown up by financial strain? It’s certainly something worth studying.

The difference in vaccine hesitancy between lower-income groups sorted by education supports the previous studies that find education improves health choices. The alternate manifestation is that people who can least afford to be sick may be more likely to make risky choices.

Advanced degrees often involve learning how to think critically, mitigate bias, and how our perception may not align with reality. That may leave people more able to make this decision, regardless of financial strain.

Critical thinking skills help us detect misinformation and even improve fairmindedness, so rather than intellect, it is a matter of understanding how to vet claims. More knowledge did not improve a person’s ability to identify misinformation, only media literacy—the ability to vet claims and assess the credibility of the source—improved misinformation identification.

Perhaps, vaccine hesitancy is one of many conclusions reached in a person’s life that is affected by these stressors. A higher income may be sufficient to overcome the hurdle that a lack of education can create, and education may be sufficient to overcome the obstacles that a lower income can generate.

Maybe it is not the traits that determine vaccine hesitancy but their effect on our ability to think but the number of factors straining a person.

College Degrees Didn’t Correlate with Vaccine Acceptance—But It Looks Like Advanced Degrees Do

A higher percentage of people over 25 with advanced degrees (anything beyond college) negatively correlated with vaccine exemptions from 2009 to 2020. More advanced degrees meant fewer vaccine exemptions.

A bachelor’s degree made some difference but not much. When we look at the Democratic states that had an increase in vaccine hesitancy, the percentage of people with advanced degrees is lower than in states with drops in vaccine exemptions.

The same difference doesn’t seem to appear for Republicans, but Republican states had significantly fewer advanced degrees on average.

Maine and Hawaii are good examples of Democratic states with lower percentages of the population with advanced degrees.

It is also noteworthy that states with a close to 50-50 split saw an increase in hesitancy.

Conjecture: This may relate to the fact that swing states are often subjected to hyper-partisan content as candidates vie for the small number of persuadable people who could hand them an election.

These are also states that can have more tumultuous policies, as flip-flopping the party in control of legislature can lead to cycles of enacting and repealing policies.

Polling data in this article about vaccine hesitancy that is without hyperlink or citation comes from this source: “American COVID-19 Vaccine Poll.” 2021. Accessed June 18, 2021. https://covidvaccinepoll.com/app/aarc/covid-19-vaccine-messaging/#/credits.

Data related to education, vaccine exemptions, and trends from 2009 to 2020 can be found here: E Rosalie. (2021). Vaccine Hesitancy Over Time 2009 to 2020. Novel Science.

https://www.hks.harvard.edu/events/epistemic-motivations-political-identity-and-misperceptions-about-covid-and-2020-election