What We Can Learn From A New Study On Congress Members’ Tweets And — Maybe — How to Save America

An analysis of COVID-19-related tweets from American political elites, researchers analyzed 30,887 tweets written in Jan and Mar 2020 shows a brief chance we had to achieve bipartisan consensus.

The bitterness chewing our nation into bits of anguish has left many uncertain about where we go from here. To say that society hinges on us navigating out of this partisan nightmare no longer seems hyperbolic. The third wave in the US promises to bring devastation, the likes of which was have never seen. It doesn’t have to be that way and stopping it doesn’t mean living under 24/7 draconian “lockdown,” either.

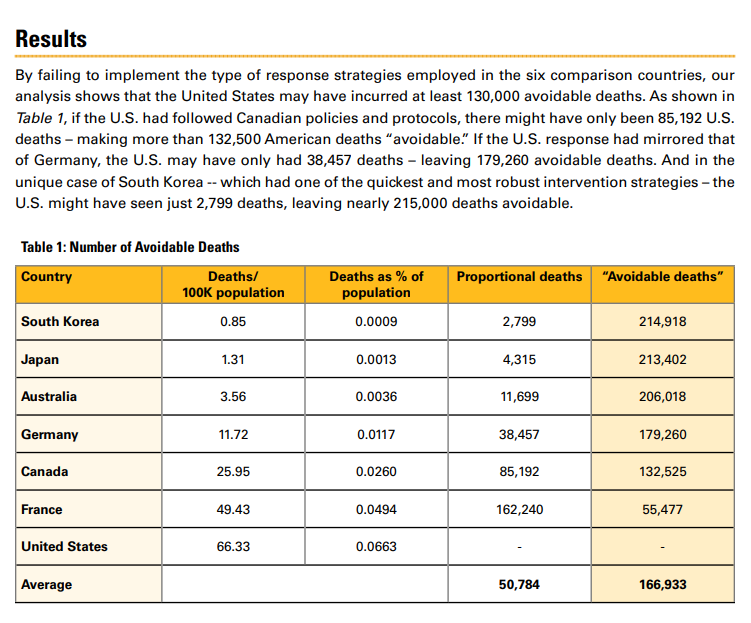

The pandemic response in the US was so poor that Columbia and the National Center for Disaster Preparedness estimate that a US response at least as competent as peer countries could have saved 130,000 to 215,000 deaths. The number defies belief because we had everything needed to prevent it, but perhaps some part of our denial is because we don’t want to believe our failures cost so much.

Alongside the data that regrettably and predictably drips with discord, I found hope. Scientists intended to observe and describe only, but in their work, I see a light that may be bright enough to guide us from this darkness.

In a study focusing on what we can learn from COVID-19 related tweets from American political elites, researchers analyzed 30,887 tweets written between Jan 17 and Mar 31, 2020. The data painted a picture of a brief period early in the pandemic where we might have achieved bipartisan consensus.

Polarization fluctuates over time, like the weather. People follow political elites, especially in crises like war. The consequence of this is if politicians divide, so too will the public. Once people's opinions form, especially in times of crisis, evidence may not be enough to change minds.

Dr. Skyler Cranmer, a seasoned political scientist and study author, highlighted a key find:

“At the outset of the pandemic, COVID-19 was not a political issue. It was not a foregone conclusion that it would become one. There was a moment when a unified bipartisan or nonpartisan consensus could have emerged.”

In an alternate reality where we united, Cranmer continued, “the result would almost certainly have been a less fractured response — both in terms of the government and individual citizens — that would have more effectively controlled the spread of the virus, saving lives, and minimizing economic damage. Given that possibility, the speed at which political polarization happened was quite disheartening.”

His words struck a somber chord for me as a public health scholar. Controlling the virus was our best hope for protecting our economy and saving American lives. Whether someone was concerned with health or business, a study from MIT looked at historical pandemic records and reported that controlling the spread offered the best outcomes for both economy and health.

In the short term staying open might seem wise, but it’s why Sweden, with its relaxed measures, failed to escape the economic downturn. The shared fate of health and economy is why Goldman Sachs and the Wall-Street Journal both concluded that our economy would remain in turmoil until we controlled the virus. It’s why our economy declined before we took action and why it remained depressed after fully opening in many states.

Uncontrolled spread hurts economies long-term, but people often focus on the pandemic control measures, mistaking those as responsible for the negative effects. It is the pandemic and not the measures to control it that are responsible. The either-or discussion of health versus economy implied that few understood we could not separate the two. We wanted the same thing.

I expected Cranmer to tell me Republicans discussed business more often, but that wasn’t what the data showed. Democrats mentioned business more often, discussed the pandemic as a public health crisis, and stressed the need for worker aid.

Republican tweets centered on China, business, and framing the crisis as a war. National identity also comes across strongly, especially concerning the coronavirus. They reference Wuhan and China three times as often as Democrats, showing “China” strongly polarized Republicans away from the center.

With approximately zero finesse, I asked, “What do you say to people who regard the study as biased or politically motivated? How did the study ensure that was not the case?”

Both political scientists Dr. Skyler Cranmer and Jon Green have a candid quality. Green explained that a computer looked for patterns in word use unique to each party, rather than looking for specific words. If one group talked incessantly about bananas and the other did not, then bananas become a polarized topic.

Comparing usage between the groups and using the differences to define polarity stops opinion from injecting into the data. My concerns about bias extinguished, so I returned to the results.

That China polarized Republicans is a fact, but how we feel about it is opinion. To form one, we need to ask more questions. What did it achieve? Did it best serve Americans in crisis?

Where the virus originated from matters little in a crisis. We rescue people from a burning building before we find the arsonist. We can prosecute equally after rescuing people, but if firefighters look for who started the fire before putting it out, many more people will die.

For many Americans, the struggle is just beginning and more than we need to know who is guilty, we need help. I struggled to make sense of polarizing around China. What end did it serve?

Then, the Corona Big Book, a political strategy guide sent to Republican senators surfaced online. The guide advised they not defend the President.

Instead, the words recommended deflecting and mentioning China. The document vacillates between racism, propaganda, and abject dishonesty. Notably, they coordinated this response but did not feel we needed coordination to combat the virus.

Put another way, they recognized the power a unified message would have on voters but did not think the outbreak warranted one.

When we view COVID-19 specific tweets versus the general tweets from congress members in the same period, we see that they polarized further, not less. Each group propelled away from the other.

Polarization peaked the week of Feb 9, 2020, a date the authors note as roughly two weeks after finding the first recognized case in the US. I think another date may have played a larger role: Feb 5, 2020.

On that day, Congressional testimony given by American pandemic experts alerted officials about the seriousness of the crisis.

“We have a travel Band-Aid right now. First, before it was imposed, 300,000 people came here from China in the previous month. So, the horse is out of the barn.”

— -Ron Klain in congressional testimony

Scientists explained that travel bans would fail, the virus was likely already here spreading, the current US policy could make us less safe, and that Congress would likely be called upon for financial aid.

The testimony polarized politicians. Americans needed action, leaders received the best advice in the world, but any action required cooperation.

The date also raises the question of why polarization happened then — the week of Feb 9, 2020 — and not after the classified bipartisan meeting on Jan 24, 2020. By then, the virus had reached US soil, and we knew it spread person-to-person.

The testimony polarized politicians, but that begs the question of why it did not earlier when many of the same people heard similar information on Jan 24?

We must explore why and what led to an abdication of duty and rejection of scientific consensus. Could any other American perform his or her job this poorly and expect to keep it, let alone receive payment while those they failed must suffer economic devastation?

Furloughing Congress until answers materialize seems just. We cannot trust people to advocate for us when they themselves are not subject to the consequences of their actions.

Cranmer pointed out, which party a person thinks is “right” is entirely subjective and not discussed in this study. The data describes what happened. The most polar term overall, “coronavirus,” indicated Republican authorship.

I recalled an earlier study that looked at reactions to the crisis by state. Republican governors were 42% less likely to mandate social distancing. Why that was the case is something we must explore without injecting opinions.

If scientists should use a different communication style for Republicans than for Independents and Democrats, we need to know. If fear of losing federal support affected them, that should be addressed.

Could poorer states have delayed for fear of subsequent economic downturn, not understanding the delay would cost more, or out of concern for children who receive meals through schools?

How a state reacted to the pandemic cannot reduce to a single variable.

Elected officials face a merciless reprisal for changing stance or breaking from party consensus. We should ask what sort of behavior we motivate with our responses and whether it’s serving us well.

Politicians changing stance or breaking with party position, often end up lambasted in the media or ostracized by their party. This says either we expect politicians to never be wrong, or we expect them to stick to their word even if new information says they should change stance.

Where one party missteps, the other presses the wound with glee.

We must see our masochistic pastime for the dysfunctional cancer that it is. We are one country — attacking ourselves.

Green put it best:

“We should be providing our elected officials with political incentives to communicate responsibly about the pandemic.

Politicians face competing pressures such that they may see it as being in their interests to discount the scientific or public health community’s recommendations.

If politicians perceive that they will be rewarded by voters for being proactive and vocal about public health best practices, others might learn from that.”

Ohioans rewarded Governor Mike DeWine with a nearly 80% approval rating at the end of summer. That’s 31 points higher than a year earlier, in a state that goes back and forth in elections, in a remarkably divided country. Bipartisan approval for Utah Senator Mitt Romney also surged, following his masked march with protestors.

Still, Utah has reached some of the highest case counts and has had to contemplate rationing care. Despite a Senator willing to break with the party line, the signal that comes from political consensus holds a power not found in scientific consensus or dissenting voices.

Governor DeWine and Senator Romney have shown that one of two is true: people value politicians unafraid of following the truth — even when it favors the opposition — or flannel masks hold an unforeseen universal appeal.

Lasting economic and societal stability comes from making choices based on evidence, facts, the truth. Defending both the evidence and those who follow it, whether it favors us in the short-term, should come before all else.

We want to play the long game, and a functional government favors us all long-term — even if you have to compromise. The alternative is no action at all. Would you like some of what you want or societal collapse?

Extreme polarity is the fruit of sown discord and if we continue to serve as fertile ground, we will reap exactly what we have sown.

You may wonder, “Where is the hope she promised back with the apocalyptic Lady Liberty?”

The hope has been there all along. She is the hope that I see, for none have called to take her down.

Even now, we can agree and we can unite, as can political officials who can put voters before self. The story shows that there was a time when polarization was not a foregone conclusion and there is always a choice.

Special thanks to Dr. Skyler Cranmer and Jon Green who answered my questions and conducted the research our country needs.

Thank you to David Malakoff, a most wonderful mentor, and human.