Task Force Doubles Down on Rapid Testing Strategy to Fight the Coronavirus

Some states say they don’t have the supplies to comply with the federal government’s advice.

by Liz Essley Whyte for the Center for Public Integrity

The White House task force is doubling down on part of its strategy for halting the spread of the virus: widespread use of rapid tests.

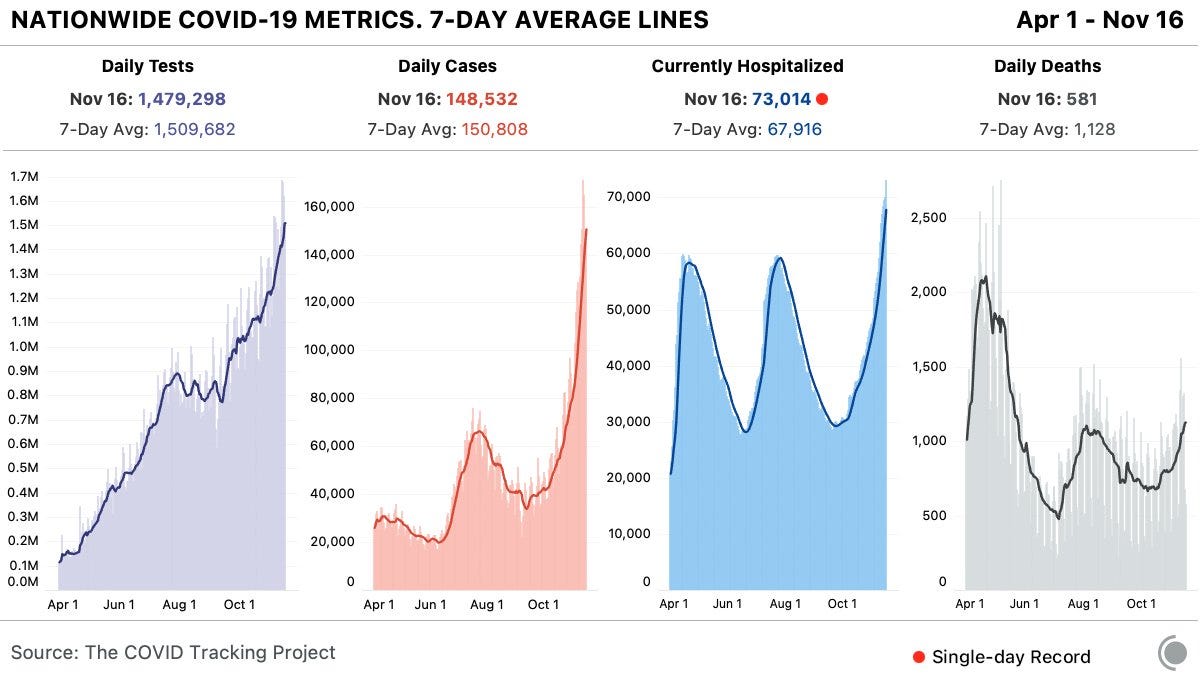

As COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations reached record highs, the task force last week issued advice to a number of governors: Begin using rapid tests on all young people, even those without COVID-19 symptoms, in counties with exploding numbers of cases. The guidance came as state officials and some scientists express doubt about rapid testing strategies.

The rapid tests, known as antigen tests, give results faster but are more likely to return false negatives than lab-based polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, and the Food and Drug Administration has not yet approved the rapid tests for use in patients who show no symptoms. But the nation’s testing czar, Adm. Brett Giroir, who also sits on the task force, gave a robust defense of the strategy in emailed responses to questions from the Center for Public Integrity.

“The testing of asymptomatic individuals with rapid antigen tests is vital,” Giroir wrote. “The data are really to a point that those who argue against asymptomatic testing … are more influenced by politics, financial self-interest of their industry, or lack of knowledge than they are by the evidence of how to support control of the pandemic.”

The task force previously urged states to use the rapid tests to screen certain groups, such as teachers or health-care workers. The federal government is distributing to states 150 million antigen tests made by Abbott Laboratories.

Giroir pushed back on comments from another member of the task force, Dr. Scott Atlas, who told The New York Times last month that testing asymptomatic people would amount to “destroying the workforce.” Atlas, a favorite adviser of President Donald Trump, holds views repudiated by many scientists studying the pandemic and has been the source of rifts within the task force.

“No credible public health expert would suggest that it is good practice to allow an infectious person — whether symptomatic or asymptomatic — into the community or workforce,” Giroir wrote.

“The best way to keep America working and Americans in school and employed is to control the spread of the virus.” But it’s not clear that states can keep up with the federal advice to deploy rapid tests more broadly.

Of the 16 states that responded to questions from Public Integrity, 11 said they were using rapid tests to screen special populations, such as nursing-home residents or health-care workers, but only four indicated plans to use them on broader populations. Several said they didn’t have enough tests to screen the general public. “We do not have enough supplies to use for general population testing,” said Taylor Gage, spokesman for Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts.

“The state is using all the tests — we do not have a reserve or backlog on hand.”

Manpower is another dilemma. Some states don’t have enough school nurses to deploy antigen test screening in schools, let alone the general population, said Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. “Nobody’s against that but some of it is just pure logistics. If you want us to do that, where are the tests?” Plescia said.

“It’s just there are sort of on-the-ground challenges to rolling some of the stuff out with the speed that the administration would like.”

Another hurdle to testing 18-40-year-olds: the millennials themselves.

Young people so far have not responded well to efforts such as contact tracing, said Lori Tremmel Freeman, CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials.“Getting them to test frequently, if this is the population we’re targeting, will require more than just putting the tests out there,” she said.

“It requires, really, a campaign to change public sentiment around the disease.” That’s something the White House has not done.

The president lately has been mostly silent about coronavirus testing, after weeks of falsely blaming high case counts on increased testing. And the task force’s recent endorsements of antigen testing are contained in reports to governors that the White House does not make public.

“We’re hearing some of the right words, the right public health tactics, the right strategies emerging from the White House task force behind the scenes, but we really have to turn that internal to an external, public-facing messaging campaign,” Tremmel Freeman said.

“Nobody really knows what the strategy is or why it’s important.” In addition to concerns about “how,” some states are hung up on whether they should use rapid tests on asymptomatic people when the FDA has not approved them for that use. Several states still have official health guidance that contradicts the White House view of rapid tests — Virginia policy, for example, says PCR testing should be used whenever possible.

At least three states have discouraged the antigen tests’ use in nursing homes. The federal government has shipped more than 13 million rapid tests to nursing homes, but a Kaiser Health News investigation found that roughly 38% of the nation’s nursing homes have yet to use them.

“There’s quite a bit of uncertainty and things we’re sorting out that have caused most of us to move forward with some caution,” Plescia said.

The health officials in his organization “just have some anxieties around the accuracy of the test.” But several scientists who spoke to Public Integrity said the administration’s push to test more asymptomatic young people using antigen tests is a good idea.

“We have to do more to break these chains of transmission,” said Gigi Gronvall, an immunologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “You could be saving somebody by testing them and getting them to isolate.”

Some cautioned that jurisdictions who deploy the tests more broadly need to have clear plans to ensure positive people isolate — which may be a challenge for those who need to show up to jobs or risk losing them.“Advocating for [antigen tests’] use really broadly without a plan for what to do with the results is going to create problems,” said Susan Butler-Wu, an associate professor of clinical pathology at the University of Southern California’s medical school.

“You have to have a plan for what to do when it’s positive, and you have to have a lot of education around what to do if it’s negative,” Giroir said states must figure out how exactly to test wide swaths of their populations, though he said weekly testing at universities has shown the best results. “States and counties need to employ strategies specific to their populations including education and resources,” he wrote.