How and Why We Must Act on Aerosol Spread, Plus the Reason for Debate

Experts to CDC: We Must Act Now on Aerosol Transmission

We must step up our response to address the nature of the threat: the aerosol spread of Covid-19. Last fall after hundreds of experts wrote a public letter asking WHO to acknowledge aerosol spread, the CDC acknowledged the risk of aerosols (viral particles that can float in the air for hours), but the US failed to adapt. Quickly the CDC pulled down the acknowledgment, saying it was a mistake.

Likely, that isn’t what happened, but that’s for another article another day.

What’s the difference between droplets and aerosol?

It’s not black and white. Few questioned whether the virus could spread through the air. Rather the debate was over how often it happened. If it was rare, then treating this virus as airborne would have wasted a lot of energy and resources.

Why couldn’t people agree on whether it could spread by sharing air?

First, scientists don’t debate to find a compromise. We dialogue to help each other find holes in our arguments, so it’s not that we’re looking for a happy medium. We’re looking for the truth. That takes time.

Still, we make the best recommendation we can with what we know. That means the recommendation must change if the new information we learn warrants it.

One disagreement is over where the cutoff between large and small droplets exists. The cutoff wouldn’t work like a magic line where everything bigger than X falls to the ground and everything smaller than X floats. It’s a continuum.

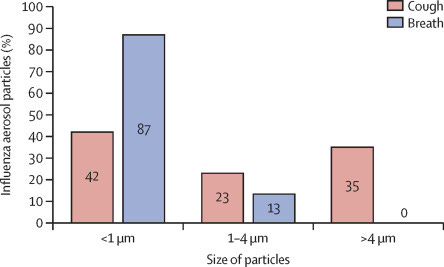

Various sources will put the cutoff at 2 µm, 5 µm, 10 µm, 20 µm, or even 100 µm—which you can read as ultra-freaking-tiny, super-freaking-tiny, teeny-tiny, itty-bitty, and small. If you prefer to be precise, µm stands for micrometer, commonly called a micron. A cough doesn’t release particles of just one size.

It’s a continuum based on the size of the particle or droplet. Droplets are larger and heavier and fall to the ground shortly after the person expels them via sneeze, speech, etc. Aerosols hang in the air because they are much lighter—a little like clouds except not visible.

To ask whether we should say the virus is airborne means also supplying definitions because otherwise, it may depend upon who you ask and how they define the terms. Getting term definitions and interviewing experts wouldn’t be worthwhile for most people at this point. We know the virus spreads through the air often enough that we should do more to lower our risk.

Distancing protects us when a virus spreads via droplets, which fall to the ground fairly quickly.

With aerosol, the drops behave more like smoke indoors, floating for hours at a time and traveling beyond six feet.

Aerosol spread means the tiny drops are floating in the air and that means fans and central air can move them. The concentration of the virus in the air depends on the size of the room and whether a window is open or another form of ventilation exists. We can see some particles in the air, like fog, but most are invisible, like dust or pollen.

Picture someone smoking in a small room with you versus outside (again, smoking is bad; I am not promoting smoking). In the room, you would inhale a lot more smoke. Introduce ventilation or a fan that blows toward the smoker and out a window, and you breathe in a lot less. The same principle applies here. We know Covid spread via aerosol. We cannot ignore that. Not addressing it will not protect us from the threat.

Ways to sharpen guidelines:

Improve indoor ventilation in all workplaces but especially high-risk ones.

Expand access high-quality masks in high-risk workspaces

Hike filtration standards for common store-bought masks to better protect the public

The DIY Covid air filter (we cannot say with certainty it helps, but many argue that it’s unlikely to do harm and may help a lot).

Before re-opening a school, administrators should have an HVAC professional examine heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) to verify it’s working properly.

Professional should confirm:

filters, dampers, as well as economizers seals and frames, are intact, clean, functional, and responsive to control signals

temperature and relative sensors are properly calibrated and communicating with the building automation system

air handling systems are providing sufficient airflow to individual rooms and exhaust fans are functional and venting outdoors.

Currently, the CDC doesn’t recommend high-quality respirators in meatpacking plants, prisons, buses, or grocery stores—and some hospital workers have no choice but to reuse N95 masks, The New York Times reports.

Why Address This Now?

Sugarcoat-free answer: These new variants are a serious problem and could prolong our pandemic lifestyle. At least one new strain appears deadlier and there are no guarantees as to how a virus mutates.

If we politicize it as we did last year, the US could see a fourth wave. We’ve already lost 500,000 people, a half-million lost lives. Many of these deaths were preventable deaths, meaning without Covid a person would still be here.

We can’t bring them back but we can do better in the present. Panic won’t help, but good information and evidence-based recommendations will. We have the knowledge necessary to navigate this.

Another reason to address this now: OSHA has until mid-March to issue emergency temporary COVID-19 standards on ventilation and masks for workplaces. OSHA will look to the CDC guidance to set its mandates, so the CDC and other respected resources on Covid must make the recommendations the evidence warrants.

“It’s time to stop pussyfooting around the fact that the virus is transmitted mostly through the air.”

—Virginia Tech’s Linsey Marr