The following was published by Being Well in November of 2020.

The US Supreme Court began work on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) case, formally known as California V. Texas, on November 10, 2020. The Trump administration and the Department of Justice (DOJ) argue that the ACA “must fall” since Congress eliminated the tax penalty for people without insurance. Whether we can sever the mandate from the ACA is the central focus of the case and a question the Supreme Court will answer.

Millions of Americans' health insurance coverage and employment hang in the balance. The stakes have risen in this case since some 14.6 million Americans had lost their healthcare coverage by June 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

How would repealing the ACA affect your state?

CAPTION: Spending cut and coverage loss numbers are from Linda Blumberg, Matthew Buettgens, and John Holahan, Implications of Partial Repeal of the ACA through Reconciliation, Urban Institute, 2016. The job loss analysis is from Josh Bivens, Repealing the Affordable Health Care Act would cost jobs in every state, Economic Policy Institute, 2017.

The mere mention of the ACA provokes partisan sentiments, but the ACA has been popular for its guaranteed coverage for pre-existing conditions, emergency care, prescription drugs, and maternity care. The US stands alone in its healthcare approach, but how the US got where it is today may hold the answer to finally achieving accessible, affordable healthcare for all.

“At present the United States has the unenviable distinction of being the only great industrial nation without compulsory health insurance,” the Yale economist Irving Fisher said in a speech in December.

December of 1916, that is. More than (a century) ago, Fisher thought that universal health coverage was just around the corner.

—Jill Lepore

Our journey began over 100 years ago, in 1912.

Apparently, we’re bad at this whole health policy business. In the beginning, Southern politicians decried the involvement of the government in healthcare. Industrial workers in America faced the “problem of sickness,” missing work because of illness, no doubt related to toxic chemical exposures and unsafe work environments.

Wage losses happened at the same time healthcare bills arrived. Consequently, in the 1900s, sickness was a major cause of poverty. It continues to drive poverty in developing countries for the same reason. By 1915, progressive reformers proposed a system like those in Germany and England.

Presidential hopeful Theodore Roosevelt included health insurance in his campaign platform and found enthusiastic grassroots support from laborers, especially women trade unionists and suffragists. Contrary to popular belief, a significant number of women have always worked, and maternity coverage would relieve them of a major hardship.

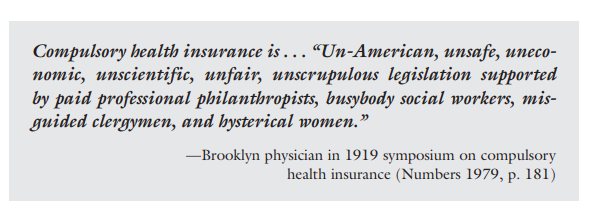

Alas, it was all for naught. The public met fierce opposition from physicians, businesses, insurance companies, and conservative legislators who banded together and labeled the effort Bolshevism. Instead, in the 1920s, advocacy groups put forth a humble proposal for voluntary health insurance. The effort met vehement condemnation from the American Medical Association (AMA), which called it “socialized medicine.”

Clearly, this discussion has moved by leaps and bounds, said no one ever.

The discussion over which healthcare payment system was best happened among the elite classes of society, in subscription journals, in political debate. No one enlisted commentary from working-class people who would likely have shared the pain of teetering on the verge of homelessness anytime someone fell ill.

Then, along came the Great Depression. Doctors and hospitals sought to ensure payment given the uncertain economic climate. This led physicians and hospitals to no longer oppose health insurance as we know it today. Harry Truman proposed national healthcare systems in 1945 and 1949 as a part of the Fair Deal to get coverage for more people.

Union workers largely already had insurance. Companies were competing over the limited workforce by offering attractive benefits packages. That meant fewer people had a vested interest in expanding access. As is so often the case, people mostly cared if they had insurance, leaving a large minority without coverage.

Truman’s effort paled compared to the PR efforts of the American Medical Association and industry lobbyists. There was too little interest and few people in power who favored the idea. Over time, as costs increased, more people got behind the national healthcare system idea, but Truman’s effort was dead-in-the-water.

How could industry keep a loyal politician in office without meeting the public’s healthcare demands?

Change the demand.

The easiest solution: Convince the public, they don’t want universally accessible healthcare.

Campaigns warned about “socialized medicine, rationing of family doctors and of freedoms Americans held so dear.”

A tad dramatic, but the public had little access to the details and had to take decision-makers at their word. Around the same time, Europe and countries of similar wealth had mature, efficient systems established. Still, the AMA warned, “any kind of government health care system would be socialist, costly, bureaucratic, a hindrance to scientific progress, and detrimental to the doctor-patient relationship.”

CAPTION: “Still Just as Hard to Swallow” is a cartoon included in a pamphlet created by the National Physicians’ Committee titled Showdown on Political Medicine, ca. 1946.

Again, Americans heard about the socialist threat that lurked behind the promise of affordable healthcare. Medicine, the last of the sciences to enter the evidence-based era, offered no support for its claims. The tragedy of this was that the industry profiting most from the existing system, with all its inherent inequality and strife, manipulated those who suffered most into rejecting precisely that which could have eased their burden.

Regardless, the public remained firmly turned off to the idea, so President Lyndon B. Johnson instead focused on the poorest populations. He hoped that by zeroing in on the most vulnerable people, he would not face opposition. The AMA suggested an Eldercare model aimed at low-income seniors. That still left a major vulnerability in the system.

Since insurers paid the bills, the shopping around ordinarily done by consumers didn’t happen. No one asked if they were being overcharged.

Prices ballooned partly because they could and partly because of scientific advances that required ever more expensive equipment. Leaping ahead through decades of much of the same back and forth, advances in research, and we’re approaching the new millennium. “The number of people without health insurance was 45.8 million in 2004, compared to 45.0 million in 2003 and 39.8 million in 2000,” making clear the problem of coverage was growing with each year, and so too did the problems that accompany a lack of insurance.

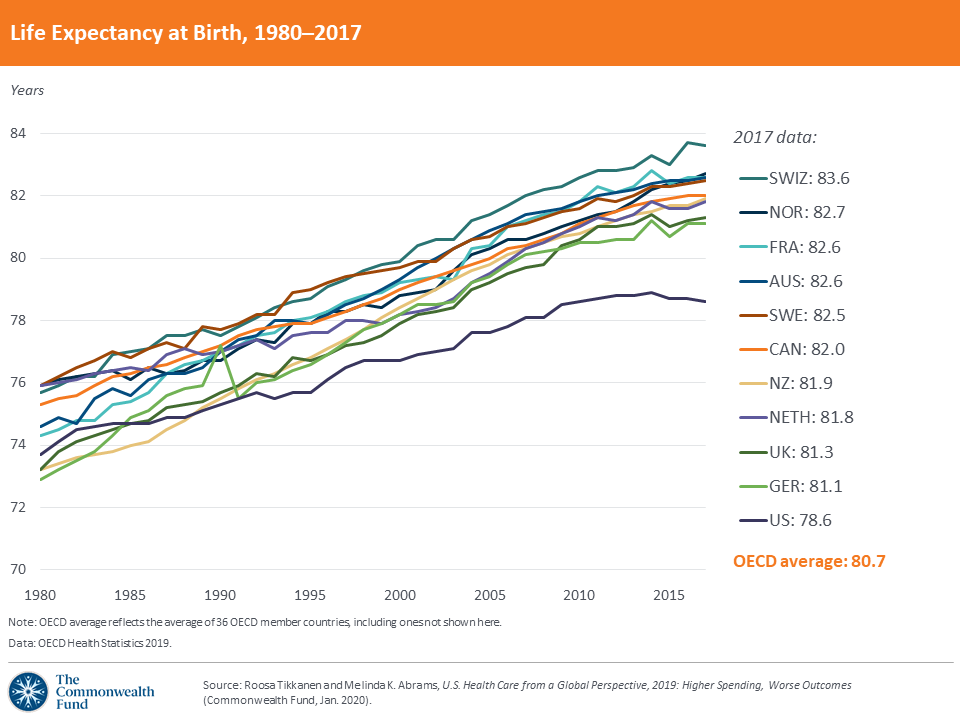

The Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice published a report in 2004, Improving Healthcare: A Dose of Competition. The federal government broke up marketing agreements and challenged hospital mergers. That did little to address the cost problem, though. Americans had spent significantly more than their most like peers since 1980. How much more only increased with time.

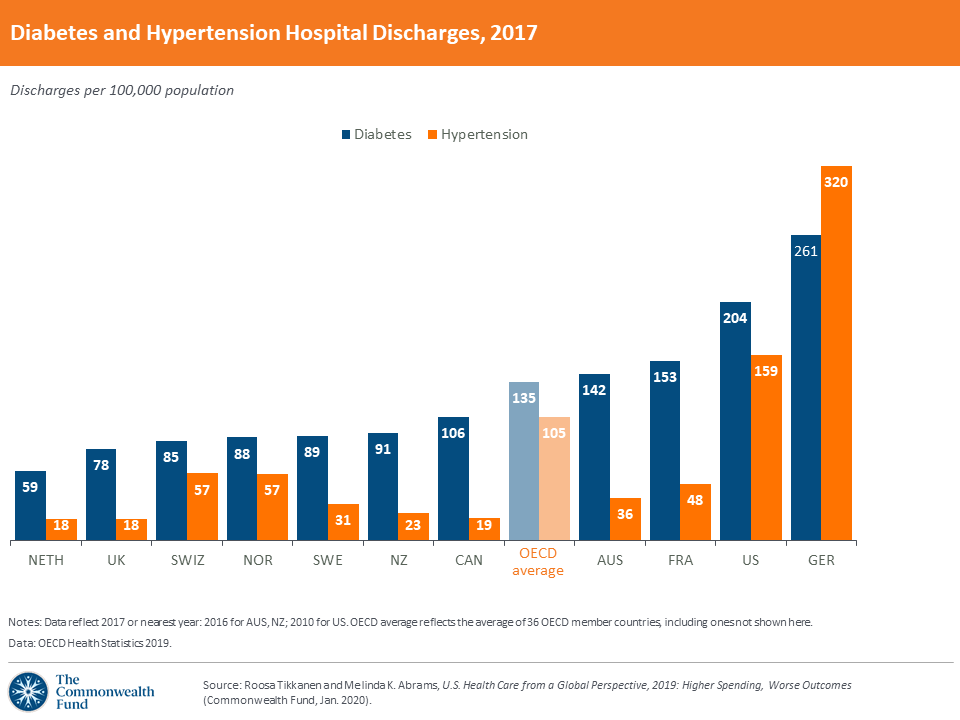

At present, Americans pay more for the same level of care or worse:

87% more than Canada

102% more than France

182% more than Japan (which has one of the highest life expectancies)

This is controlling for all factors, so it’s comparing apples to apples, as they say.

Enter the crisis of astronomically priced healthcare and fewer Americans having access to it, people avoiding treatment until it required urgent, expensive care, and we’re not far off from the situation in the early 1900s with the “sick worker problem” and poverty.

While many know the ACA as ObamaCare, with all the partisan disdain that accompanies that, the policy that provided the foundation for the ACA came from a conservative who devised it for fiscally conservative reasons. The foundational policy, RomneyCare, was the work of Senator Mitt Romney, who was a Republican governor at the time.

Yes, the one-day Republican presidential hopeful came up with the plan to address a budget crisis in the state of Massachusetts. Uninsured people often wait too long to seek care. Then, when pain or discomfort finally drives someone to address the problem, often the state was on the hook for the astronomical medical bills.

Even if the bills had not been sky high, this approach still left uninsured people with higher rates of chronic disease and accompanying treatment costs, disability, and overall poorer health. Uninsured people die earlier, sometimes because they catch hypertension only once it’s done damage or because they missed the chance to catch conditions like cancer early.

The problem was that Medicaid excluded a population that wasn’t low enough income to qualify, but that also couldn’t afford insurance through work. To make insuring everyone possible, healthy people, who often gamble by not having insurance, and sick people, would all have to join. Mandating coverage was the critical aspect that allowed a system to protect people with preexisting conditions.

“Insurers, meanwhile, would no longer be allowed to deny coverage based on preexisting conditions. The individual mandate and protecting people with preexisting conditions — went hand in hand. With a huge new pool of government-subsidized customers, insurers no longer had a financial incentive for trying to cherry-pick only the young and the healthy for coverage.

And the mandate would prevent people from gaming the system by waiting until they got sick to purchase insurance. Touting the plan to reporters, Romney called the individual mandate “the ultimate conservative idea,” because it promoted personal responsibility.”

— an excerpt from Annals of the Presidency, November 2, 2020

Senator Romney’s experimentation with a state-level policy reduced the uninsured population to 4%. Deaths among the 20 to 64-year age range dropped 2.9%, and deaths from preventable conditions dropped by 4.5%.

Still, the system was much too costly. Likely a function of inventing the wheel, Romney’s plan suffered many of the cost inefficiencies that plague our system today. A later study in the Annals of Internal Medicine that assessed the program said of the cost: “…there are likely to be policies out there that could save a lot more lives than RomneyCare does per dollar spent.”

Indeed, other policies and the relatively small population in MA likely contributed to some lackluster fiscal rewards. Large populations are essential for making the policy work. People who stay healthy longer generate GDP and cost the government much less. They catch cancer early and live. Insured people may have more money to invest in their children, thus paying out in future generations. The scenario in the early 1900s also suggested that it could help with poverty, but that was still a theory.

This was superior to the scenario where people developed chronic illness and disability and remained unable to work or recover. Regrettably, the US persisted with the latter model.

Grim realities born of the inequities began to appear.

Enter President Obama. The ambitious young President saw that starting from scratch would be far too disruptive to the economy and seemed likely to offend conservatives. Instead, he proposed something similar to RomneyCare. Getting something passed was more important to Obama than a perfect plan.

He was a son troubled by the early death of his mother, who may have lived had she had access to care earlier. The ACA wouldn’t bring her back, but he reasoned that it might save someone’s mother or father or sister or brother. We would have less suffering, less death, and likely spend less while finally giving Americans what our peers have had for a century.

One of the early objections claimed that rationing and “death panels” would surely result, though no one provided evidence for the claim. The concern also failed to recognize the 45,000+ Americans sentenced to death each year from preventable diseases we can easily treat.

We cannot treat what we don’t know is there. Commonly, Americans hear of cancer cases where a person chooses not to seek care, fearing the debt they might leave behind. The fear of disregarding the value of human life in old age via “death panels” consumed the public discussion — and not by mistake.

A similar story played out as it had in the 1950s and 60s. The senate minority leaders sought a well-known political strategist named Frank Luntz to help convince the public to oppose the policy. Luntz studied which words could turn public opinion.

Just as they had in the 1950s and 60s, Americans responded with strong, albeit irrational fear, toward a “government takeover of medicine.” Luntz work found the message that affected the public the most was this:

“No Washington bureaucrat or healthcare lobbyist should stand between your family and your doctor. The Democrats want to put Washington politicians in charge of YOUR healthcare. We can and must do better. Say no to a Washington takeover of healthcare and say yes to personalized patient-centered care.

In reality, the act only expanded care. The policy included nothing approaching “government takeover,” but that message, along with the “death panel” schtick, seriously weakened the public support. Earlier conciliatory negotiations with the pharmaceutical industry meant that Obama had neutralized that threat. He agreed to leave out the ability to bring in prescriptions from Canada in exchange for no opposition.

Finally, the votes needed for the ACA came through, and the act narrowly passed on November 7, 2009, by a vote of 220–215.

Since 2017, Congress has spent a great deal of time attempting to repeal the act, but looking at its impact, it’s unclear what upright motivation could exist. The program cost 25% less than projected, and states found an economic benefit in multiple sectors, not unlike we sometimes see in developing countries that gain care access.

Other surprises appeared: poverty rates fell significantly in expanded areas, food security improved, and people defaulted on fewer loans. The whole-of-society benefit that ACA proponents hoped for began to appear.

Shortly after the election of President Trump, the House attempted to pass the American Health Care Act. The bill’s main impact was that it removed protections for pre-existing conditions: “Under current law, health insurance companies can’t refuse to cover you or charge you more just because you have a “pre-existing condition” — that is, a health problem you had before the date that new health coverage starts.”

Only by the vote of late Senator John McCain did Congress fail to repeal it. That act had a profound impact on the lives of Americans who would not go without care, and without something to put in its place, it seems obvious why McCain opposed.

Now, again the ACA hangs in the balance. There is no Senator McCain, only the Supreme Court with its freshly minted judge. Though the Republicans claimed they had no intention of removing protections for pre-existing conditions, that conflicts with their repeated efforts to do so in the past four years.

An estimated 54 million people have a pre-existing condition that could have resulted in them being denied coverage in the pre-ACA individual market. That falls on top of the 14.6 million that lost coverage by June 2020. That’s a population much larger than many countries.

In the last four years, drug prices have stayed the same or risen despite promises to lower prices, meaning the uninsured would have little hope of a greater ability to afford healthcare expenses. AP analyzed 4,412 brand-name drug price increases and 46 price cuts for the 2018 year. For increases to decreases, it was a staggering ratio of 96 increases per 1 decrease.

To date, no one has put forth a viable healthcare policy to put in the ACA’s place, despite actively trying to remove it. Like many Americans, I’ll be crossing my fingers. Opening arguments began on November 10, 2020.